Novel writing and blogging don’t go together, at least not when you’re on a deadline. I emerged from my post-deadline sleep to discover that the notes from the pulp I’d been reading before it all started, Someone to Love, were mysteriously missing. It was no loss really. The heroine’s dull heterosexual adventures (leavened by one moment of homosexual panic) as she searches for love, pale in comparison to…

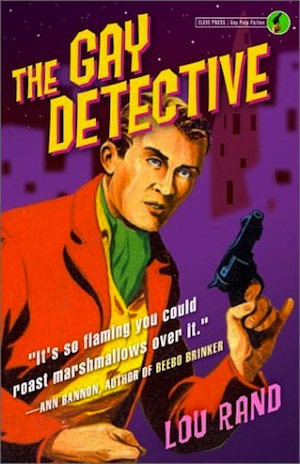

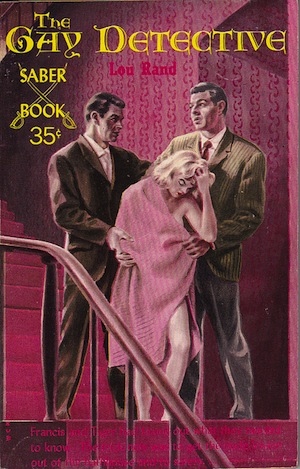

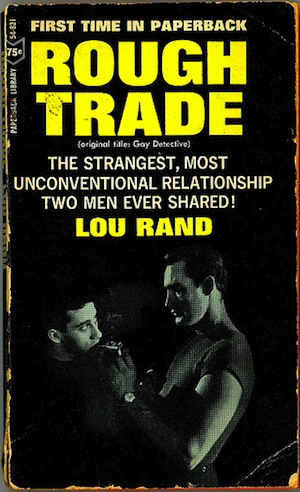

The Gay Detective, by Lou Rand, Saber Books 1961.

Reissue cover blurb: “It’s so flaming you could roast marshmallows over it.” — Ann Bannon

(note: This book is an enjoyable page-turner, and the 2003 Cleis reissue makes it more available than many pulps (check your local library too). So if you think you might want to read it, skip the spoiler-filled plot summary below.)

The Plot: Bay City is rife with crime. On the novel’s opening page, two men, brutish Buster and fey Kay, dump a body into the ocean. Meanwhile, the movers and shakers of Bay City — Senator Martin, Captain Starr of the Police Department, Bert Kane the columnist, and nightclub operator and gambler Joe Cannelli — are in the backroom at Flanagan’s, joking about how their city needs more ferries on the Bay and fewer on the street. Talk naturally turns to Francis Morley, a new arrival in Bay City, who has inherited his uncle’s detective agency. “A very pretty fellow,” says Captain Starr dubiously.

Ex-chorus-boy Francis waltzes “lissomely” into his new office in the next chapter, pondering “this gay, gay city that offered so many opportunities for companionship.” His first business decision is to redecorate, to the dismay of Hattie, his uncle’s efficient secretary. His next is to place an ad for an assistant that reads: “Young man wanted — rough, tough, attractive.” The constantly camping detective hires ex-football star, ex-marine Tiger Olsen, and then takes him boxing, to “knock out” any queer notions Tiger may have about his new boss.

As Francis settles in, Buster and Kay are busy blackmailing a man in a deserted park. When their victim protests, Buster kills him, and after Kay helps him dump the body, shoots Kay too, and arranges the corpses to make it look like a murder-suicide.

The police are flummoxed. They know that the murder-suicide is a fake (the old gun in the right hand of a left-handed guy mistake) but the victims are “practicing homos” and the cops aren’t having any luck infiltrating their world. Captain Starr decides to use Francis, since he’s “possibly a nervous type.” He sends the newly-minted detective a client, Vivien Holden, sister of the first victim, Arthur. Francis turns her over to Tiger, suggesting the pair look for Arthur’s diary, while he goes to headquarters to inspect the body.

Tiger and Vivien forget about the diary as they get acquainted, first in Tiger’s car, then Vivien’s bedroom. While they satisfy their “burning loins” (I should start counting how many times I run across that phrase), Francis is examining Arthur Holden’s corpse, and instantly sees what the police missed: the absent underwear, the key on the rubber band — they all point to one thing: Arthur was killed at Dave’s baths, and then dumped in the ocean!

This leads to the meat of the book: Francis’s and Tiger’s night-long party during which they “pretend” to be “practicing homos” in order to infiltrate the sinister bathhouse. Francis plays the well-heeled out-of-towner, and Tiger the rough trade he’s picked up for the night.

At Joe Cannelli’s Bait Room they watch a drag show and pick up some of “the local girls.” From there it’s on to an after-hours joint called The Gourmand where “You can get anything from a piece of trade to a mainline shot.” As they smoke marijuana cigarettes and chat up the waiter, they discover the connection between Kay and Buster, and learn that Buster is currently at Dave’s Baths. “Off to the baths, girls!” Francis carols gayly.

In the back room at Flanagan’s Captain Starr is having a drink with Senator Martin, wondering if he’s done the right thing, trusting this flighty newcomer. Senator Martin inquires about the investigation, and is interested to learn that victim Arthur Holden left a diary.

Back at the baths, athletic Tiger attracts the attention of the attendant, “Stepladder Kate,” a self-described “kind of madame.” He tries to convince Frances and Tiger to put on a sex show and make a few bucks, and when they turn him down, proposes that Tiger pose for some “art” photos — muscle magazine type stuff. Tiger agrees — only so that the intrepid detectives can check out the off-limits upper floors. Kate leads Tiger to a bedroom decorated like a DeMille set, and tricked out with concealed cameras and mirrors that are really one-way glass. Waiting for the photographer, Tiger chats with an older man who recognizes Tiger and says that “Bruce would raise his prices” if he knew the ex-football star was posing. Before Tiger can inquire further about the mysterious “Bruce,” Kate cancels the photo shoot; Buster, the photographer, has been unexpectedly called away. The weary detectives head home.

Francis is still recovering from his night on the town when he hears that Vivien Holden has been kidnapped. Putting two and two together, he concludes that someone heard about Arthur’s diary and kidnapped Vivien to get hold of it. It must be Buster, he thinks; that’s why he was called away from the photo session. And he must be holding Vivien at the Baths!

This threadbare reasoning is enough to send the detecting pair back to the bathhouse, where they conk out the attendant and split up to search the place. While Tiger “rescues” Vivien, who is having a good time with Buster in the DeMille room, Francis finds the office and collects incriminating photos, letters, and coded ledgers. He burns the first two and pockets the third, along with some cash. Buster interrupts him just as he’s set fire to the pile of paper in a handy clawfoot tub. Despite being outweighed by brutish Buster, Francis uses judo (the gentle way) to defend himself, and with a well-timed hip thrust, sends Buster through the window, plummeting to his death, like Madge in Dark Passage. The two detectives and “victim” Vivien emerge from the bathhouse as it goes up in flames.

The denouement restores Bay City to its normal state. Vice has not so much been driven out, as put back under wraps, where it belongs. The murders are officially solved, and Vivien has departed on a cruise. Francis deduces that “Bruce,” the mastermind of the blackmail scheme was Senator Martin, and that Captain Starr engineered the senator’s death to avoid a scandal. He plays along with the police, pretending that Buster was the only one involved. Captain Starr praises the pair’s detective work and admits he was wrong about Francis. To which Francis “gushes: ‘Oh Captain Starr! I bet you tell that to all the boys!'”

Sex: Innuendo galore, starting on page three, when after helping dump the body, Kay reminds his murderous partner, “You promised, Buster, if I helped” and the two then climb in the back seat of the sedan for a brief interlude. The more detailed sex is strictly straight — the burning loins of Tiger and Vivien, and the s/m encounter between Vivien and Buster, which goes on for three pages, as Tiger watches through the one-way glass, not shocked but “enthralled and almost unbelieving.” Buster tells Vivien that she’s just like her brother, who liked to be whipped. The voyeuristic Tiger is also fascinated by the two marines he sees embracing at the after-hours club. On being asked if they ever come up for air, the waiter explains they’ve been at it for an hour and now are “just saying goodbye.”

Drinking: Other vices are more interesting in this book. Francis makes it through his long night by pretending to drink, and dumping the drinks under the table when no one is looking. Tiger tries a marijuana cigarette, and seems to inhale quite deeply.

Homo Psychology: Pragmatism prevails. None of the characters care how homos came to be, and the book is refreshingly free of bad mothers and painful teenaged experiences. The only question is, now that they’re here in Bay City, what to do with them? “Live and let live,” says Joe Cannelli, and Captain Starr agrees — better to let the homos congregate and blow off steam than arrest them. Even the FBI man admits, “these people aren’t actually criminals.” Vivien has “studied social services” in college and is reconciled to her brothers predilections. She adds, “He isn’t the extreme type. There isn’t anything particularly noticeable or ‘gay’ — I think that’s the common expression now — about Arthur.” Indeed, flamboyance is what makes people uncomfortable in this book, not gayness per se. The world is divided between nelly queens and butches (gay and straight), with Francis veering between the two in an endless “is he or isn’t he?” tease.

History Lesson: In the Cleis reissue’s excellent introduction, historians Susan Stryker and Martin Meeker give readers the skinny on Saber Books, an obscure paperback publishing company run by two gay men (one a member of the Mattachine Society) and based in Fresno, California. They put out sleazy, lurid books and were eventually charged with obscenity for the sale through the mails of Sex Life of a Cop. When I consulted Murder Can Be Fun’s John Marr about Saber, he remembered that their books used to carry little updates on the court case. The legal struggle put an end, alas, to any possible sequels to The Gay Detective, even though Francis, Tiger, and faithful secretary Hattie seem poised to take on a new case at the end of this book. Lou Rand was actually Lou Rand Hogan, who I first encountered when editing Forever’s Gonna Start Tonight. In the 1970s he wrote a column for the B.A.R. called “The Golden Age of Queens.” The Cleis edition introduction has more about Hogan, as well as fun speculations about which real San Franciscans the characters in The Gay Detective are based on. I’m still searching for more information about Saber Press, the only gay pulp publishers (as opposed to writers) that I’ve come across.

Comment: This is a tight, if threadbare, mystery plot, told at the speed of a bike racing downhill, featuring gay content and innuendo on every single page, if not in every paragraph. The mid-century coyness coupled with endless camping boggles the mind. It’s like a twisted version of don’t-ask-don’t-tell; as long as Francis never says he’s queer, he can flame around Bay City like an oil-dipped torch. But who cares? Rand skips the endless soul-searching of the more turgid pulps and goes straight for the pervy fun. The appeal of this book, for me, is the constant stream of gay chatter, a glimpse of camp from the era when it flourished, written by a knowledgeable insider. It’s kind of like stumbling across the transcripts of a lost tribe’s idle conversation, from the days before they were studied to death by anthropologists. This is camp before it was killed by academics like Susan Sontag whose “Notes on Camp” I read as a teenager without ever realizing that she was talking about a gay subculture.

Of course, I don’t know for sure whether or not this is how (some) conversation sounded in the Black Cat back in 1961 — maybe the snappy dialogue is just Lou Hogan’s wild imagination at work. At any rate, the pages overflow with female pronouns applied to male characters, and are full of expressions like, “Get you, May!” “Get you, doll!” “Come on girls, let’s live it up!” By the end of the book, the camp style has even infected the supposedly straight Hattie and Tiger. When Tiger flips his wrist and tries a “Whoops to you!” Francis spells out mid-century queer role division: “Let me do the camping in this act. I’ll make with the gay talk. You just be big and beasty.”

cover photos from jeffandwill.com who have a nice gay pulp paperback cover of the week feature on their site.