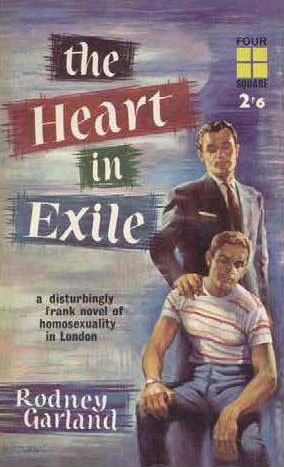

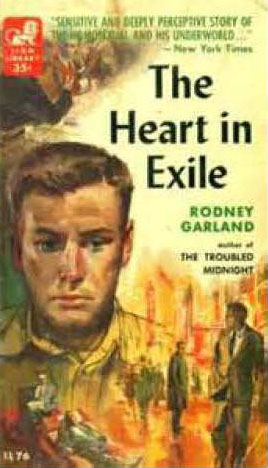

The Heart in Exile by Rodney Garland, W.H. Allen 1953

The Heart in Exile by Rodney Garland, W.H. Allen 1953

Cover line: A disturbingly frank novel of homosexuality in London

I discovered this gay British novel, not precisely a pulp but on the pulpy end of the spectrum, through a citation in my favorite book of 2015, The Spiv and The Architect. “Queer novels of the 1950s frequently exploited the continued currency of the traditional moral economy of furniture and design as a useful device for highlighting the domestic propriety of their respectable ‘homosexual’ protagonists,” wrote author Richard Hornsey, using The Heart in Exile as his example. He ties the novel’s detailed description of a bachelor flat to the way “a specter of malignant queerness haunted modern design,” leading to the perception of modern furniture as “an agent of corruption that would seduce children from the normative rituals of family life.” Who wouldn’t be intrigued?

The Plot: The suicide that ends many pulps starts this one. Tony Page, a queer, currently celibate psychiatrist takes on a new patient, Ann Hewitt. Ann is distraught over the suicide of her fiancé, Julian LeClerc, particularly after she discovers an intimate letter in Julian’s flat, signed “Gina.”

Little does Ann know that her doctor and Julian were once lovers. In ruthless disregard for all medical ethics, Tony pumps Ann for information, visits Julian’s flat, and interviews Julian’s colleagues and friends, all under the guise of helping Ann recover from her grief. Initially Tony is panicked that Julian might have left evidence that will expose his own queerness; but as his anxiety is relieved, his curiosity about just what pushed Julian over the edge increases.

It’s obvious to Tony as soon as he sees the letter that “Gina” is actually “Ging” or “Ginger” not the “other woman” but the “other man”. Inspection of Julian’s flat uncovers his photo; concealed behind the framed portrait of Ann on the mantel is a picture of “what some people call the Butch type.” This must be Ginger, thinks Julian. A working class bloke, the kind “middle-class inverts look at with nostalgia.”

Picture in hand, Tony makes the rounds of London’s homosexual underworld, a milieu he once knew well, looking for Ginger. He calls up old friends, goes to the current gay pubs — “these meeting places of the underground changed all the time, like the offices of clandestine newspapers” — dines at the house of commons, drinks at a gay club, and attends a theatrical party. This is the point of the book — this tour of London’s secret homo world, filled with slang, gossip, and insider explanations of its workings. “Inverts are everywhere,” declares Tony, proving it by calling on the queer underground’s man in Scotland Yard for some investigative aid. Was Julian being blackmailed? Had he been caught in a raid? Was he on one of the Yard’s unofficial lists? The answer is no.

Picture in hand, Tony makes the rounds of London’s homosexual underworld, a milieu he once knew well, looking for Ginger. He calls up old friends, goes to the current gay pubs — “these meeting places of the underground changed all the time, like the offices of clandestine newspapers” — dines at the house of commons, drinks at a gay club, and attends a theatrical party. This is the point of the book — this tour of London’s secret homo world, filled with slang, gossip, and insider explanations of its workings. “Inverts are everywhere,” declares Tony, proving it by calling on the queer underground’s man in Scotland Yard for some investigative aid. Was Julian being blackmailed? Had he been caught in a raid? Was he on one of the Yard’s unofficial lists? The answer is no.

Tony latches on to a promising lead when a fat man in a pub tells him that Julian had had an affair with a printer named Tyrell. By a crazy coincidence, printer Tyrell Dighton is Tony’s “star patient”–Tony is curing the lad of homosexuality. At the next appointment, with his usual lack of ethics, Tony quizzes Tyrell about Julian, who Tyrell knew as Nigel: “I should like you to tell me about Nigel. What you say may reveal some of his motives for suicide. But of course, that’s not the reason I’m asking you to tell me about him.”

The only thing Tony concludes from his unorthodox analysis is that Julian dumped his lower-class lover because Tyrell was inching towards the middle class, going to night school and working on losing his Yorkshire accent. Julian wanted the real thing — the mysterious Ginger.

Julian’s oblivious law partner provides another letter, this time with an address, which finally leads to Ginger. Ginger turns out to be a married fellow named Stan Atkins, an old flame of Julian’s from the war — but he’s not the guy in the picture.

Who and where is l’homme fatal? “He might be a merchant seaman,” Tony thinks, “He may have been a soldier, an airman, a stevedore, a brick-layer, a barrow-boy. Maybe he was in jail. Or maybe he was in London, living a couple of minutes away from me.”

After wading through rumors and red herrings, Tony gets the dirt from fey playright Everard: Julian was in love with a young tough named Ron Ackroyd. Yes, he says, when Tony shows him the picture. That’s the guy. “I hear he can always be found in one of the queer pubs, sitting alone.”

Tony finds Ron at the Treble Bob. “I’ll tell you everything,” says Ron, providing the psychiatric investigator with yet another case history. Julian was Ron’s first gay love and Ron was the butch boy of Julian’s dreams. After a blissful beginning, however, Ron couldn’t handle Julian’s fairy friends and they broke up. During this hiatus Julian got engaged to Ann. But when he and Ron reunited, as was inevitable, Julian decided to break his engagement and live with Ron. One night as the two were returning to Julian’s flat, they encountered an older man waiting for Julian. Two days later Julian was dead. Ron doesn’t know who the man was, but Tony recognizes him from Ron’s description as Julian’s father.

Tony confronts the old man who says he knew two men, from such different backgrounds, together, late at night, could only mean one thing. He admits that he ordered Julian to give up his homo friends and marry Ann or else face exposure. And so Julian killed himself. “It wasn’t my fault,” the dad tells Tony, begging him to agree.

Naturally, Tony’s investigation and discoveries shake up the good doctor, and lead to some soul-searching about his own queerness. Should he marry wealthy Ann (transference having done its job) and make another attempt to be “normal”? His star patient Tyrell has fallen for a woman — maybe Tony can too? And what about Terry, his also-gay-receptionist/housekeeper? Tony’s attracted to Terry, especially when he spies him scrubbing the floor in his undershirt, but he worries the relationship would be too easy.

The investigation and his master’s distraction have also disturbed doglike, devoted Terry. Usually careful, Terry accidentally breaks a casserole and a china horse. “Which meant only one thing, as anyone with the slightest acquaintance with the subconscious would have realized at once.” Tony thinks. “Terry was jealous.”

Two pages from the end, Tony realizes he’s in love with Terry. “I was a psychologist. I recognized the symptoms.” He says goodbye to Ann, instructs Ron to return to heteroville, and tells Terry he’s taking him to France for a vacation, rendering the dog-like boy “almost numb with happiness.”

Sex: Elided. Remembering his affair with Julian, Tony skips directly from Julian putting his arm around Tony to their post-coital conversation. Other inverts’ memories of romps with gondoliers, visiting “low bars” or picking up sailors are equally sketchy.

Sex: Elided. Remembering his affair with Julian, Tony skips directly from Julian putting his arm around Tony to their post-coital conversation. Other inverts’ memories of romps with gondoliers, visiting “low bars” or picking up sailors are equally sketchy.

Drinking: They drink, but the point of all the pub crawling is sex, not intoxication. Ron gets drunk after Julian’s death. Tony chokes down some stewed tea while questioning Ron’s mother, under the pretense that he’s an inspector for National Health.

Homo Psychology: Tony feels “no guilt, no doubts, no uneasiness” when he takes up with Julian. After their breakup he decides to “be normal” and has sex with girls only to realize that while he can enjoy the heterosex, he can’t love women. “This was not because they were women,” Tony adds somewhat confusingly. Maybe because they’re not men? When his father dies during WWII Tony goes “abnormal” again, and has a gay old time for three years. Then he ponders religion and morality, deciding the promiscuous life is wrong. But he can’t fall in love. Why not, you ask? I don’t know. This is one of those English books that delight in not saying crucial things. For example, Tony is asking his supervising psychologist, Dr. Weblen, if he can be cured. “I’m going to ask you a very important question,” says Dr. Weblen. “Yes,” says Tony, knowing what he’s going to say before he says it. Well, Tony may know, but I sure don’t, in that instance and a whole bunch of others. Dr. Weblen tells him he’s gay because of his “unresolved narcissistic components,” but that he’s a better doctor for it. This compensatory view of homo-psychology, wherein homos are both stunted and extra gifted, is common to homo apologias of this period.

The pansy bashing is also typical: “such people are usually unintelligent, verbose, neurotic and generally tiresome.” To balance this negativity, Tony tells us that inverts can be brave (providing WWII examples), and later notes that some inverts have “a feminine elasticity” which makes them good social climbers.

Class: The gay obsession with class was a new wrinkle to me. All of Tony’s upper-class friends talk about the lower class endlessly, discussing their mysterious appeal: “We don’t want anybody who shares our standards, I mean educated, middle class and so on,” says a stockbroker pal. “We want the very opposite. We want the primitive, the uneducated, the tough.” This pairing of opposites seems to operate in this book as rigidly as butch-femme role playing did in lesbian America in the 50s. Other kinds of couples make brief appearances, but this is the paradigm. Meanwhile, the heteros in the book, Ann and Julian’s law partner Mohill, regard the working class as as if they were a separate species, exotic and possibly dangerous. Both admire Julian’s ability to “get on” with such people.

The Contemporary Critics: In his foreword to the reissue, Neil Bartlett calls the novel, “a perfect crash course in the prehistory of British gay culture.” He sees the novel as mixing the conventions of the crime thriller and the problem play, resulting in a genre “halfway between the fictional sensationalism of Dorian Gray and the sensationalist documentation of The Wolfenden Report and then wrapping the whole thing up in the would-be sophisticated tones of a minor rainy afternoon Celia Johnson vehicle.” He adds, “The emotionally tortured post-war queen is of course an acquired taste. Personally, I love them.”

The Contemporary Critics: In his foreword to the reissue, Neil Bartlett calls the novel, “a perfect crash course in the prehistory of British gay culture.” He sees the novel as mixing the conventions of the crime thriller and the problem play, resulting in a genre “halfway between the fictional sensationalism of Dorian Gray and the sensationalist documentation of The Wolfenden Report and then wrapping the whole thing up in the would-be sophisticated tones of a minor rainy afternoon Celia Johnson vehicle.” He adds, “The emotionally tortured post-war queen is of course an acquired taste. Personally, I love them.”

“The novel has historical importance as the first mystery with a gay sleuth, and the tropes that it introduces are the major ones that still govern gay writing, mystery and non-mystery alike. Its obscurity seems mysterious in and of itself; it should be required reading.” Drewey Wayne Gunn for Lambda Literary.

My Take: The Celia Johnson film comparison is dead on; like Brief Encounter the story takes a melodrama and wraps it in a depressive dreariness. Tony’s weary, disenchanted tone makes it easy to forget that there’s actually a happy ending for our last-minute gay couple. Which the author balances by returning both Tyrell and Ron to the safety of heterosexuality.

The best parts of the book are when Tony is cruising the underground with his upper-class (or middle-class, or striving bounder–I can’t pretend to parse these class distinctions) gay friends. Here’s Tony observing the gay pub scene: “Two middle-aged businessmen entered now, and as they walked to the bar they took a brief inventory, almost like housewives at a remnant sale.”

However, as a guide to this subculture Tony is drip, a bore, a party pooper nattering on about neuroses while the fellows around him gossip and flirt. Terry deserves better. Let’s let him have the last word: “If ever I could write a book on the subject [queerness] I’d try to tell the truth. I’d write about the majority for whom it isn’t really tragic.”