Once upon a time I was attempting to summarize my books for a friend of my brother’s while my niece and the friend’s two kids ran around my brother’s living room wreaking havoc.

In the midst of my long-winded dissertation on lesbian pulp fiction, its historical context, my attempts to reimagine it, etc, my brother looked up from his iPhone and interrupted.

“Actually, they’re like these Beany Malone books we read when we were kids.”

Busted!

Of course my brother would be the one to out me. As a former member of the Beany Malone fan club (one meeting, one newsletter, six members all bearing the same last name) he is intimately acquainted with Lenora Mattingly Weber’s unmistakable literary style and fictional techniques, from which I have borrowed freely.

Of course my brother would be the one to out me. As a former member of the Beany Malone fan club (one meeting, one newsletter, six members all bearing the same last name) he is intimately acquainted with Lenora Mattingly Weber’s unmistakable literary style and fictional techniques, from which I have borrowed freely.

How to communicate the appeal of LMW and her most famous creation, Beany Malone? How to acknowledge their seminal influence on me as a person and a writer? I’m not the only one who owes her books to Beany. So maybe you’ve already heard of Beany. Maybe you’ve read the books. But if you haven’t, I’m here to help. Let’s Meet the Malones!

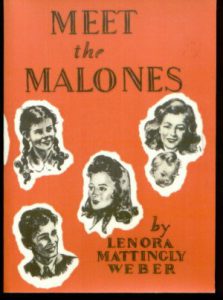

Meet the Malones, by Lenora Mattingly Weber, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1943

Meet the Malones, by Lenora Mattingly Weber, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1943

Classic line: “I’m through being a nice, well-meaning kid!”

Beany is only a secondary character in this first Malone tale. Her older sister Mary Fred takes center stage in a narrative that LMW will repeat with variations throughout the series. This is the pattern: one or more Malones are tempted away from their old-fashioned values by the siren song of luxury, arriving in the shape of a new formal, a private rumpus room, or a fancy wedding. Initially the heroine resents her mundane lot and longs for a more glamorous life, only to realize that such worldly vanities are hollow, unsatisfying, and that she is actually happier “scurrying around” cooking for others instead of going to a party; and that she prefers wearing an off-the-rack dress over a designer creation. To scurry and to bustle in these books are sure signs of moral good health.

The Plot: In Meet the Malones, the Ur-version of the LMW narrative, the Malone kids need money. High school junior Mary Fred has bought a lame horse, Mr. Chips. Johnny, a boy-genius writer at fifteen, is saving for a new typewriter and has to pay damages for a fender bender with an egg farmer. Thirteen-year old Beany wants to replace the childish rabbit wallpaper in her bedroom.

Because money is tight in the Malone household (although Dad Martie Malone has a steady job as a well-known newspaper columnist, money is in short supply throughout the whole series), their widowed father makes a deal: the three kids can take over for the departing housekeeper; he’ll gives them a lump sum every month and they get to keep what they don’t spend on groceries.

This happy scenario of bustling around independently, shopping, cooking, cleaning, etc. is interrupted by two things. First, Dike Williams, “the biggest big wheel” in high school, starts giving Mary Fred a rush. Mary Fred soon tires of going home to starch shirts when it means turning down Dike’s invitation to be his “squaw” for the French Club party. Earning horse feed for Mr. Chips begins to pall. This is temptation number one.

Then Martie, the most morally superior father since Atticus Finch, goes off to Hawaii to report on the war, which makes everyone feel bleak. Scarcely has he left when oldest sister Elizabeth knocks on the door with a newborn baby (no she’s not a single mom, she’s married to a serviceman) come home for the duration.

Into this chaotic household cruises temptation number two, Nonna, aka Mrs. Gaylord, aka the Malone kids’ step-grandmother. A sophisticated (always a bad sign in these books), soignée business woman who looks vampirishly young for her age, she’s sold her decorating business in Philadelphia and has come to take care of her motherless grandchildren. “It looks as if our work is laid out for us here,” she tells her faithful secretary-assistant, Hattie, as she starts showering presents on the bedazzled kids—clothes for Mary Fred, a brand-new typewriter for Johnny, and a room makeover for Beany.

Nonna thinks the housekeeping business is “foolish and unnecessary.” Faithful Hattie takes over and Mary Fred is sleeping in and going off to school with a lunch someone else has packed. Nonna also stops Johnny’s payment to the egg farmer—the farmer has no legal claim on Johnny, Nonna tells him. A debt of honor you say? What nonsense!

Do you see the deadly poison in this red, polished apple of luxury? I hope so. The new formal, the typewriter, the wallpaper all come with a hidden price tag. The Malones have given up their independence and self-respect; they are weakened like the cosseted Manchus, ripe for enemy takeover. “Have you Malones learned the salute yet?” sneers Emerson Worth, an old newspaper colleague of Martie’s, after a visit. Yes, the fairy-god mother is actually Hitler in disguise.

Nonna soon reveals her true colors. She sells Mr. Chips while Mary Fred is at school, and when she redecorates Beany’s bedroom, it’s her way, not Beany’s. Beany takes down Nonna’s store bought curtains and puts up her own handmade ones in a stirring foreshadowing of all the DIY craftsiness to come. Nonna punishes the thirteen year-old by locking her in her room.

The luxe life is is a prison. Beany hates her “jeune fille” room, Johnny can’t type on his new typewriter because he feels so guilty about welshing on his debt to the egg truck lady, and Mr. Chips is being whipped and otherwise maltreated by his new owner. Dike, it turns out, is using Mary Fred, dating her in the hopes that her father will use his influence to get Dike a football scholarship.* Life is very bleak indeed. Even Elizabeth doesn’t want to use the bassinet and fancy layette Nonna purchased, preferring the simple flannel onesies she and her husband saved their pennies to buy.

But how to get rid of this tyrant they invited into their midst? Has Nonna’s sinister influence weakened the Malones irredeemably?

Fear not. Helped by a slew of refugee children from Hawaii and England, Mary Fred and the Malones find the courage to stand up to Nonna. When Nonna tries to send the sickly kids to an orphanage, Mary Fred tells her, “Father sent them to us, so of course we’ll take care of them.”

Democracy is restored and the tyrant is driven out. Ander buys back Mary Fred’s horse, Johnny pays off the egg lady by selling the typewriter Nonna bought him, the plaid curtains stay hung in Beany’s room, and all is right with the world. Nonna flees the noise and overcrowding at the Malones, hoping to repurchase her old redecorating business (see Joan Crawford in The Best of Everything), admitting that she’d “better stick to color schemes and textiles, rather than other peoples’ lives.” Mary Fred turns down a dance with Dike at a mountain lodge realizing she is “happier doing things at home.” Martie returns from Hawaii, having missed all the moral turmoil as usual, and makes a patriotic speech about the war effort as Mary Fred chokes up with happiness.

*There’s a whole subplot, where Mary Fred discovers that Dike is using her, and has to pretend she doesn’t care, and gets Ander to take her to the spring formal, and Nonna buys her a super fancy dress, and Dike gets interested in her for herself, but its kind of beside the point.

Parties: The Spring Formal; a square dance with soldiers; the French Club shindig

Clothes & Décor: Let’s just admit it, the clothes are half the pleasure of reading these books. Nonna’s first gift to Mary Fred is a “Love of a skirt,” “pleats in front and back with shades of gray and green and enough yellow to go with her yellow sweater.” Beany’s vision for her room: Yellow plaid curtains and a matching ruffled dressing table skirt. Mahogany stain on the furniture. Walls painted a shade of blue between Robins egg and the color of the sky in August, or maybe the Virgin Mary’s gown. Nonna’s jeune fille redo: furnishings of modern bleached wood, curtains and bedspread of sheer, yet silken chartreuse material. Pink paint job (“Desert Coral” Nonna corrects Mary Fred) with a border of roses and cherubs. Do you blame Beany for taking down the greenish-yellow curtains and covering up the cherubs? Sophisticated, Nonna calls it. That word again! Nonna arrives in a silvery fur, lapis lazuli earrings matching her eyes, and a black hat framing silvery hair. The black hat should have tipped the Malone kids to what was coming. Mary Fred’s formal has “a black lace bodice and a pale pink cloud of a skirt. There was sure sophistication [italics mine] in the way the dress was cut low to the waist in back, in the long, snug fitting sleeves.” She also gets a new blond fur evening coat with shell pink satin lining.

Slang: De-Gee: praise for a boy, from “the guy”. Studes: “spectacled grinds with high grades.” Mop-squeezers: The ones who do the “grubby, behind-the-scene jobs,” like working extra in domestic science to bake cookies for mother’s day. Queens: the girls who dance, carefree, reading news about themselves in the school paper put out by those grubby studes and mop-squeezers. To compliment Mary Fred, Dike calls her “a straight-arm stagger.”

Prices Back Then: Mary Fred purchases Mr. Chips, the lame riding-horse, for $30. Johnny pays for 48 dozen broken eggs at 29 cents a dozen — $13.92. Mrs. No-Complaint Adams, the departing housekeeper got $40 a month, plus $60 for groceries. A new pleated wool skirt costs $5.95.

The Moral of the Story: “The highest price you can pay for something is to get it for free.” Readers know right away that Dike is a bad egg because he trades his sports stardom for free clothes and theater tickets. Meanwhile Elizabeth gives birth in Wyoming, by herself, without even calling her dad because: “In times like these everyone has his own burden.” I guess labor and delivery weren’t covered by the army back then. Martie pretends he wants to give his kids the material goods they long for, but actually, “my reason tells me it’s a blessing I can’t.” Hattie says: “Kindness makes slaves and weaklings of people so much easier than unkindness.”—she has been enslaved by Nonna’s helping pay for a needed operation. Turns out this fiscal conservatism and rabid independence (Ayn Rand would smile on the Malones, except for their unfortunate tendency to help the ill and weak) is what makes our country great. Ander says: “I’ve always heard that phrase ‘of the people, by the people, for the people,’ but doggone if it ever made real sense until I sat there with you folks and saw that your family was a democracy.”

The Critics: “The Malones are certainly worth meeting,” said The New York Times in 1943. “And if the story occasionally verges on the sentimental, this is more than offset by the tonic tone of the whole.” One reviewer for The Library Journal criticized it as “Highly improbable tale with too many unreal situations” (I think she meant the orphans) and dismissed it: “Not recommended.” However another reviewer for the same publication called it a “Lively story,” concluding, “Not necessary, but will be popular, especially with girls twelve to fifteen.” She was right.

My take: Funny to think I’m almost as old as Nonna, who’s 49. Rarely has a career woman been as vilified as Nonna is throughout the series (by the time you reach Something Borrowed, Something Blue, she’s utterly irredeemable, without even the “I’m better with textiles than people” excuse). I bought the Malone kids’ independence when I first read the books — the fantasy of teenagers running their lives without adult supervision (Dad is gone at least 70% of the time) was a big part of the stories’ appeal. Beany and Mary Fred are like mini-adults: they shop, cook, clean, work extra jobs, buy horses when they feel like it — it’s a wonder they have time for school. However I find it a bit tedious that the importance of independence lessens considerably when it comes to dating. “I’d like you better if you were a little scared,” Ander tells Mary Fred, as Mary Fred sallies off to the dance, full of confidence in her new dress and ready to show Dike she’s not crying on her pillow over him. After Ander buys back Mr. Chips, Mary Fred tells him humbly, “I like you to boss me.” Who’s an obligated slave now? Mary Fred marries Ander years later, in between Something Borrowed Something Blue and Come Back Wherever You Are.

Aside from my antipathy for Martie one of the worst most neglectful parents on the planet (in this day and age he would have been turned over to Social Services for leaving 3 kids on their own..would have made a nice newspaper headline) My gripe is with Elizabeth who seemed incapable of lifting a finger around the house while the other 3 were running themselves ragged to take care of the household her and her baby