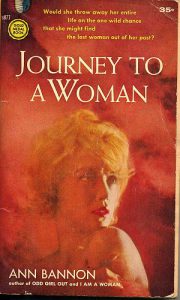

Journey to a Woman, by Ann Bannon, Fawcett Gold Medal, 1960

Journey to a Woman, by Ann Bannon, Fawcett Gold Medal, 1960

Classic Line: “All the dormant fires of her younger days had sprung to life and they burned in her still, tempting her, torturing her until she knew she would have to find release somewhere or die of it.”

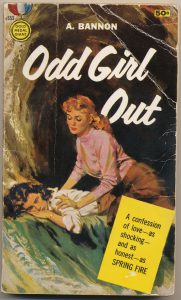

It took me many years to appreciate Ann Bannon’s contribution to lesbian literature. Bannon wrote five pulps between 1957 and 1962, linked novels that tell the intertwined, melodramatic adventures of Laura, Beth, and Beebo. The books made her the community’s best known lesbian pulp writer, and an acquaintance with her books is as much a requirement for lesbians as is knowing about The Well of Loneliness (we may not actually read these books, but we recognize the references). Although Bannon stopped writing as her daughters grew up–yes, the Queen of Lesbian Pulp was a married woman when she penned her tales of twilight love–her books lived on. Naiad Press (founded by Barbara Grier, a Bannon fan from her book review days at The Ladder) reissued the whole series starting in 1975, replacing the original lurid covers with blue-on-white silhouettes of women wearing seventies hairstyles.

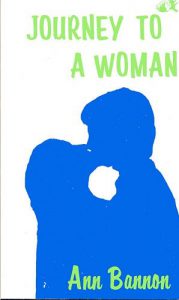

It was the Naiad edition of Journey to a Women that introduced me not only to Ann Bannon but also to the world of lesbian pulp. The seventies feminist cover I saw when I pulled the book off the shelf of my dorm common room in 1985 did not prepare me for the heavy-breathing soap opera I found inside, a style so foreign to our irony-heavy 80s sensibility that my friends and I passed it around, reading bits aloud, snorting with laughter. Snorting with laughter, yes, but unable to stop reading until we’d followed the story through increasingly over-the-top twists to its happy conclusion. I read the other books in the series and even made a film inspired by them, but it’s only after diving into the world of lesbian pulp that I realize how ground-breaking Bannon really was.

It was the Naiad edition of Journey to a Women that introduced me not only to Ann Bannon but also to the world of lesbian pulp. The seventies feminist cover I saw when I pulled the book off the shelf of my dorm common room in 1985 did not prepare me for the heavy-breathing soap opera I found inside, a style so foreign to our irony-heavy 80s sensibility that my friends and I passed it around, reading bits aloud, snorting with laughter. Snorting with laughter, yes, but unable to stop reading until we’d followed the story through increasingly over-the-top twists to its happy conclusion. I read the other books in the series and even made a film inspired by them, but it’s only after diving into the world of lesbian pulp that I realize how ground-breaking Bannon really was.

I chose this particular book for Bannon’s Pulp & Pep debut because in addition to the sentimental associations (those halcyon college days!) I’ve always preferred Beth to wimpy, whiny Laura and super-butch Beebo. Journey to a Woman is the chronological end to the series, a kind of survey and summation of lesbian life in all its Greenwich Village variety; and it’s the only book in the series that features all three characters.

Laura and Beth in their college days

The Plot: The book opens with Beth crying in bed next to her sleeping husband, an introduction to three chapters mixing married misery and backstory. Beth lives with her husband Charlie and their two small children near Pasadena. She’s another dissatisfied housewife (see One Touch of Ecstasy and Stranger on Lesbos), bored, lonely, feeling trapped. Unlike these earlier housewives, however, Beth has already had a lesbian fling. Now the college love she left behind is showing up in her dreams and Beth starts wondering: did she make a big mistake when she ditched Laura to marry Charlie?

The book follows Beth’s attempts to answer that question. First she pursues Vega Purvis, the sister of Charlie’s business partner Cleve, an ex-model with one lung and half a stomach who drinks her dinners. Beth is “dangerously delighted,” when Vega proposes getting together, and zips off to Vega’s modeling studio despite Charlie’s objections. After a stop at a beatnik cafe where Vega points out the local lesbians (“They’re disgusting, I can’t bear to look at them”) they end up at Vega’s house for an afternoon of drinking with her blind, incontinent mother and cat-hoarding grandfather. Only someone as desperate as Beth would decide that this gothic family group is “a little daffy, but in a macabre sort of way they were fun.”

Cleve disagrees, warning Beth away from Vega. His sister’s no good, he tells her. In addition to being an unstable alcoholic, she’s queer, but doesn’t realize it. Plus, she’s mother-dominated, and “Mother hates queers.” If that weren’t enough, an unsavory scandal has her modeling studio going broke. Cleve claims he wants to protect Beth: “You’re as wholesome as cherry pie, you’re no neurotic, self-blinded Lessie.”

But Beth has an “uncanny feeling that what he really wanted was to keep them apart,” and her interest in Vega is only sharpened. When Vega calls her in the middle of the night wondering if Beth could bring her a bottle of whiskey, Beth hops in the car. As they drink, Beth blurts out what Cleve has told her. Vega corrects Cleve’s analysis–she does know she’s queer, but she can’t stand being that way. Beth argues that their love isn’t wrong, but Vega says, “You only say that because you want it!” Indeed, persistent Beth is on the verge of having her way with Vega when the ex-model throws open her peignoir and reveals her scar tissue. Beth is completely revolted, and Vega tries to jump out the window. Beth pulls her back from the window ledge and forces herself to make love to Vega, to calm her down. “I knew you were better than the rest!” says poor, deceived Vega.

Now, in addition to her other problems, Beth is saddled with a nutcase girlfriend she’s no longer attracted to. “This affair was all your idea, Beth,” Vega tells her. “You insisted, I surrendered. And now you’re obligated to me.” Unbalanced Vega does not realize that duty is not a turn-on. Beth distracts herself by reading everything she can find about lesbianism, corresponding with lesbian pulp authors, and dreaming of Laura, who’s looking better than ever. After having it out with Charlie one night about her “dissatisfaction,” (“I can’t help myself, that’s the awful part”) Beth goes looking for Laura, who she now sees as the solution to all her problems. She abandons Charlie and the kids (“I want them, but I want my freedom more!”), asks Cleve to say so long to Vega (“Tell her I’m sorry, okay?”), and makes her way to New York, after a stop in Chicago to see Laura’s estranged father, who points her towards Greenwich Village.

In New York Beth hooks up with her pen pal, lesbian pulp author Nina Spicer, who shows her around, taunts her, and finally seduces her, introducing Beth to “a thousand sensual subtleties….all the tricks and caprices of a lovely body.” After two days in bed with Nina, Beth returns to her hotel and finds a letter from Cleve saying that Vega is in Camarillo (the state mental hospital) after losing her business following another scandal. Beth holes up for a few days of self-reproach, before heading back to Nina’s. But Nina has a new girl in bed with her, Franny. That night the three of them go bar-hopping; Nina taunting Beth and Franny, Franny slipping Beth her phone number, and Beth asking everyone if they know a girl called Laura.

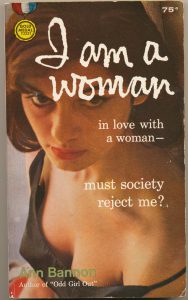

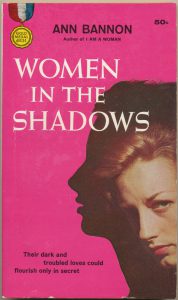

Finally, when she’s quite drunk, Beth spots handsome super-butch Beebo and repeats her question: “Do you know Laura?” Does Beebo know Laura! They lived together for two years (I am a Woman, 1959; Women in the Shadows, 1959) before it all went to hell. Beebo tells Beth that Laura is married, and when Beth staggers at the news, Beebo takes the shaken woman back to her place and gives her the skinny: Laura’s married to a gay man, has a daughter, and plays around with girls on the side.

Finally, when she’s quite drunk, Beth spots handsome super-butch Beebo and repeats her question: “Do you know Laura?” Does Beebo know Laura! They lived together for two years (I am a Woman, 1959; Women in the Shadows, 1959) before it all went to hell. Beebo tells Beth that Laura is married, and when Beth staggers at the news, Beebo takes the shaken woman back to her place and gives her the skinny: Laura’s married to a gay man, has a daughter, and plays around with girls on the side.

Beth heads uptown to Laura’s apartment the next day. Bannon subjects us to delay after delay before we get to this long-awaited meeting. Jack, the helpful husband, invites Beth to stay the night (Laura’s out with a girlfriend) and and surprise Laura in the morning. But the wait is worth it; one look at each other and the exes float off to bed in a happy cloud of nostalgia. A few hours later, the idyll is over. Once Laura has lived out every rejected lover’s fantasy–to have your ex show up begging to take you back–she’s done. She laughs at Beth’s crazy expectation that they can pick up where they left off, and refuses to play guru when Beth begs her to solve her problems. They quarrel. Laura throws a glass of water on the hysterical Beth. Beth bursts a feather pillow, and ravages Laura on the wool rug. Laura advises her, “you don’t need me, you need yourself.”

Beth heads uptown to Laura’s apartment the next day. Bannon subjects us to delay after delay before we get to this long-awaited meeting. Jack, the helpful husband, invites Beth to stay the night (Laura’s out with a girlfriend) and and surprise Laura in the morning. But the wait is worth it; one look at each other and the exes float off to bed in a happy cloud of nostalgia. A few hours later, the idyll is over. Once Laura has lived out every rejected lover’s fantasy–to have your ex show up begging to take you back–she’s done. She laughs at Beth’s crazy expectation that they can pick up where they left off, and refuses to play guru when Beth begs her to solve her problems. They quarrel. Laura throws a glass of water on the hysterical Beth. Beth bursts a feather pillow, and ravages Laura on the wool rug. Laura advises her, “you don’t need me, you need yourself.”

Unable to face this home truth, Beth returns to her hotel where another letter from Cleve awaits. this one tells her that Vega has vanished and Charlie has a detective following his wife. The double whammy sends Beth on a bender of epic proportions, bar-hopping, blacking out, and waking up naked in strange beds with girls whose names she can’t recall. After nine days of this she comes to in Beebo’s apartment. Beebo has rescued her from some dive, and even washed and ironed the stinky suit Beth has been wearing for more than a week. Beth weeps about not knowing who she is, and Beebo reassures her that “the puzzle works itself out.” She even escorts Beth back to the hotel, which Beth has been avoiding, for fear Charlie will show.

Charlie doesn’t, but while Beth is napping Vega comes out of the closet with a gun, and terrorizes Beth for a day and a night, before shooting herself in the head the following morning. Beth is arrested on suspicion of murder but is eventually exonerated because the detective Charlie hired bugged the room, inadvertently documenting the suicide. Charlie comes to town to collect Beth and take her back to California. Beth finally says it: “I want a divorce!”

Determined to start her new life honestly, she visits Laura to tell her what she’d concealed on her first visit–that she isn’t yet divorced, that she’s abandoned her kids, that she’s had another lover. She’s sure Laura will despise her for lying, but Laura excuses her–“Everything you’ve done these past few weeks you’ve done in a fog”–and they sit sipping “fragrant coffee” like two neighbor ladies in a Folgers commercial. Beebo arrives to joins the coffee klatch, then invites Beth to stay with her–“A hotel is no place for you right now.” Beth accepts, and as they exit the apartment and the book, Beebo confesses she’s fallen for Beth. “Beebo’s eyes promised that glorious undeserved chance at contentment that Beth had no right to expect from fate. But there it was.”

Whew! See why we couldn’t stop reading?

Drinking: I got a hangover just reading this book. On top of the usual never-ending stream of cocktails, there’s alcoholic Vega, who needs a bottle of whiskey with her in bed, and Cleve, who delivers his warning over multiple martinis. Beth drinks with Laura’s dad, with Laura’s husband, with Nina; Beebo “forces half a glass of whiskey and water” down Beth to medicate her shock at Laura’s marriage. And then there’s Beth’s big bender: “She had another drink. And another.” After coming out of a blackout she goes to a diner. “She settled for pastrami on rye. As an afterthought she ordered a beer….it went down well and she ordered another.” (I was humming Johnny Cash’s Sunday Morning Coming Down as I read). Best of all is the scene where Beth offers gun-toting Vega a drink.

Sex: Beth disparages herself as yokel, but she gets around. Sex starts out iffy with Charlie (“sometimes unbearably lovely…but that was only sometimes and sometimes was not enough.”) then goes downhill with Vega (“There was the fatiguing necessity of pretending to enjoy it.”) before making an ambivalent comeback with Nina, both violent (“a flash of pleasure, as sharp and dreadful as a sword impaled her”) and proto-lesbian-feminist (“The enormous force of a woman’s ecstasy flowing unfocused through her whole body, claiming her absolutely”). There’s soul mate sex with Laura (“She had the feeling, whenever Laura touched her or moved with her, that no one, no living human being, had ever understood her so beautifully”) which turns rough two pages later (“It all came together inside her and exploded in bitter kisses, sharp bites, and sudden agonized passion”), before Beth concludes with a string of one-night stands she can’t remember.

Homo Psychology: The causes of variance vary. Vega’s domineering, homophobic Mom is clearly to blame for her daughter’s twisted lusts: “Mother runs her life…Vega adores her as much as she hates her.” Incest lurks in both Vega’s and Laura’s backgrounds. “They were abnormally close,” Charlie says of Cleve and Vega, after several hints that Cleve wants Vega for himself. Pop Landon takes the blame for Laura’s gender preference: “his perverted love for her had twisted her whole personality.” Beebo is your classic invert, more masculine than a man, down to the way she snaps a match. As for Beth, she doesn’t have the excuse of incest or a bad mother, or being built tall and brawny. Perhaps that’s why she asks endlessly, “Am I gay? How do you know your gay?” After all, she is the “normal” one in Odd Girl Out, the girl who happily goes off with a man after her twilight fling. This book undermines the whole notion of normality by revisiting Beth nine years after her “happy” ending. Now the “normal” one is questioning everything while the “real” lesbian has found contentment in a companionate marriage with a gay man. It’s the world of lesbian pulp turned topsy-turvey. Beth asks Nina if her love for Laura makes her gay, and Nina replies like a post-queer millenial teenager: “For the time being…why are you so anxious for a label?”

Barbara’s take: “This is Miss Bannon’s fourth Lesbian novel and perhaps it is her best to date. It is clear that she is becoming a spokesman for her people.” (The Ladder, 1960)

Ann’s take, 2002: “Beth was a woman who needed women, heart and soul, and didn’t know how to give herself permission to reach out to them.” In her introduction to the Cleis reissue the author adds, “Her problems are the ones I was wrestling with in my twenties, especially the awkward relationships skewed by chaotic, unsorted emotions.” Bannon notes that she regarded the books as “throwaway stories,” and had no suspicion that they would be her most lasting legacy. Such knowledge, she says, “would have made them more carefully crafted, but also immeasurably more cautious….instead they are flawed and full of life.”

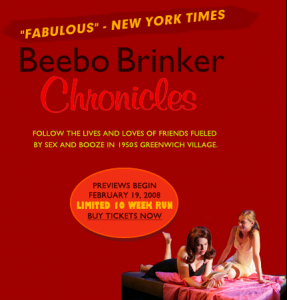

My take: This is a modern coming out story, nested inside a pulp explosion. Bannon touches on alcoholism, suicide, incest, bad sex, rough sex, glorious sex, infidelity, one night stands, torn slips, mysterious bruises, mental institutions, abandoned children, bad housekeeping, butches, femmes, johns, private detectives, girls who pass, girls who marry, insane girls with guns–in all, the most complete grocery list of lesbian pulp topics a housewife ever compiled. It’s bursting with lesbian action, like a breakfast cereal bursts with vitamins. And yet I was also reminded of John Sayles earnest film, Lianna, whose unhappy housewife also discovers that forging a lesbian identity means more than acquiring (or recovering) a female lover. And while the melodrama and plethora of loony lesbians make this book the L-Word’s grandma, there are flashes of perceptive observation throughout, as when Beth feels “suspended between two worlds belonging to neither.” Sure, the writing can be as clunky, as you might expect from a book written to be thrown away, but Bannon must be forgiven much, if only for her ground-breaking depiction of Beebo. For the first time a butch character is presented not as a pathetic freak, but like a glamorous rock star, swaggering into the bar and making all the girls swoon.

The Beebo Brinker Chronicles, a stage adaptation of the novels, premiered in New York. My friends and I were ahead of our time with our group read-aloud.