There’s a treasured shelf in my collection of mid-century teen fiction and career girl books. It holds those rare voumes in which the burgeoning civil rights movement of the sixties collides with the whitebread high school fantasies of the fifties to form a schizophrenic hybrid of the malt shoppe romance and the problem novel. It’s culture clash, Y-Teen style.

|

|

|

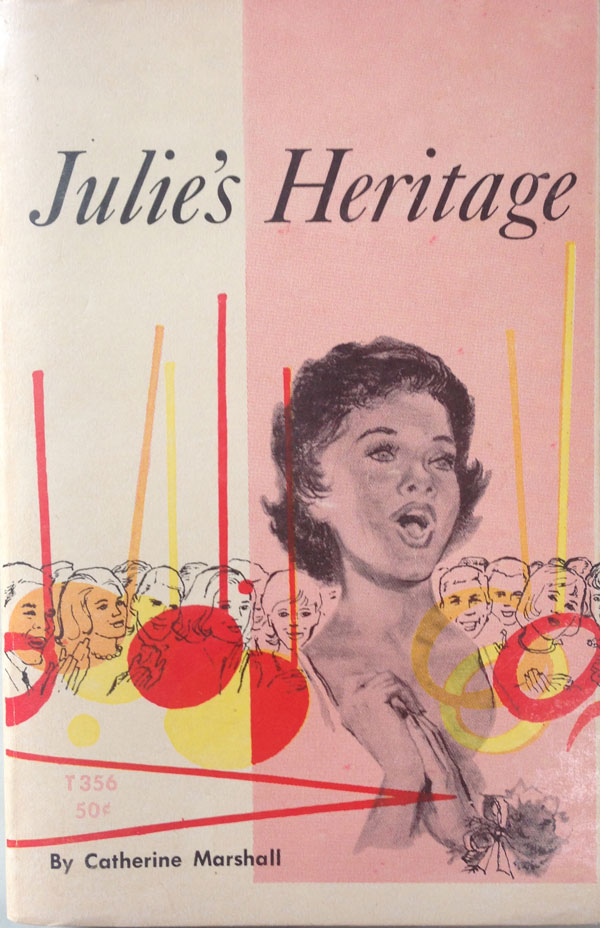

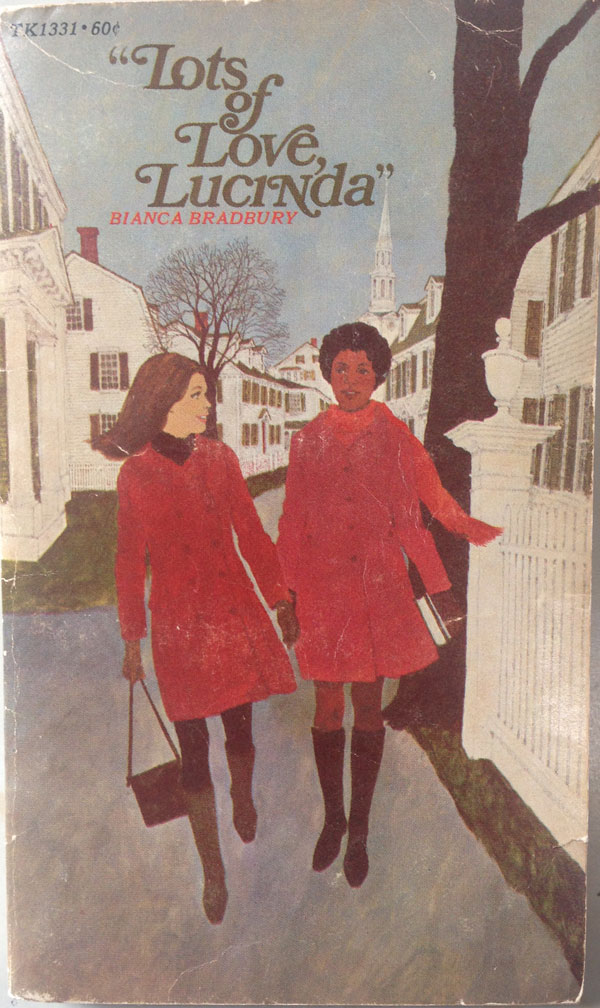

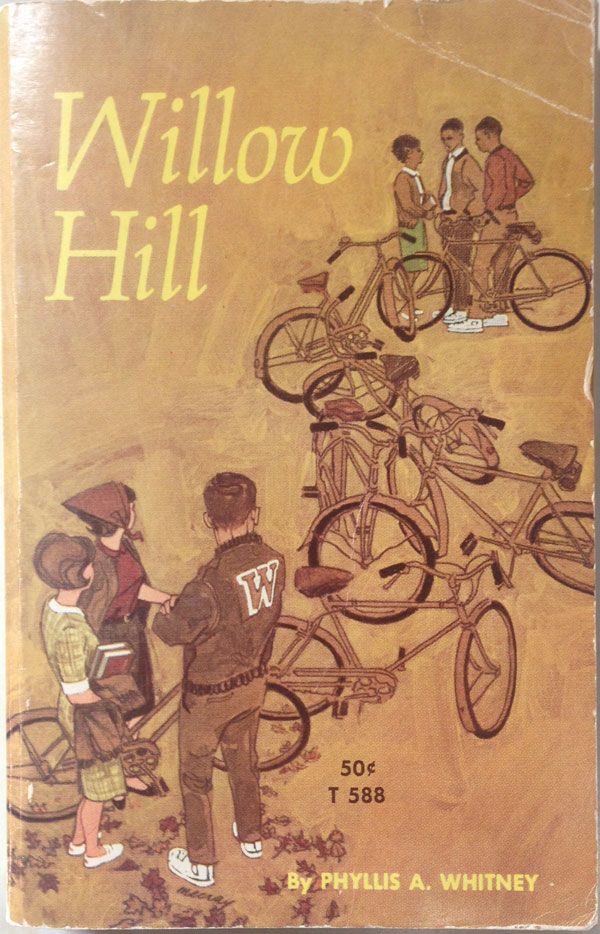

Titles include Julie’s Heritage (a black high school girl grapples with racism and dating), Why Did You Go to College Linda Warren? (good-girl Linda gets embroiled with anti-war activists during her first year of college), Lots of Love, Lucinda (Corry’s white family invites a black student from the south to stay with them and go to school in the North), Willow Hill (Val’s highschool is integrated when a new housing project gets built) and Buenos Días, Teacher (Jennifer gets involved in social protest when she teaches at a rundown school in a Mexican-American neighborhood).

The gem of this special shelf is Margaret Pitcairn Strachey’s Where Were You That Year? wherein college girl Polly Masterson travels south to register black voters in Mississippi. Now seems the right time to look back on this peppy call to action. For like Polly, aren’t we all wondering what we will tell our future children when they ask what the hell we were doing to fight injustice in 2017?

Classic Line: “I’m now a part of the most exciting thing that is taking place in the United States today!”

Plot: Little Polly Masterson surprises everyone when she decides to join the voter registration movement in Missisippi, far from her Seattle home. Her parents have never taken her seriously. Social-worker sister Joan disparages the volunteers as “half-baked kids.” Boyfriend Hank thinks Polly is motivated by a crush on another activist. But it’s idealism that fuels Polly and sends her ridesharing her way south with three other volunteers, alternately learning the lyrics to “We Shall Overcome” and worrying about who Hank took to Sally’s party.

Plot: Little Polly Masterson surprises everyone when she decides to join the voter registration movement in Missisippi, far from her Seattle home. Her parents have never taken her seriously. Social-worker sister Joan disparages the volunteers as “half-baked kids.” Boyfriend Hank thinks Polly is motivated by a crush on another activist. But it’s idealism that fuels Polly and sends her ridesharing her way south with three other volunteers, alternately learning the lyrics to “We Shall Overcome” and worrying about who Hank took to Sally’s party.

During orientation and training in Batesville, Polly learns about non-violence, the movement history, pores over A Pictorial History of the Negro, participates in bull sessions on racism, and prepares for the violence and harrassment she can expect in the field. Shortly after Polly successfully role-plays the proper defensive measures to take during an unfriendly traffic stop, the trainer gives her the green light. “I’m now a part of the most exciting thing that is taking place in the United States today!” thinks Polly.

Polly is sent to Lee, where she lives in the Freedom House with a rotating roster of other volunteers, organizes a black youth group, sorts clothes for giveaways, and takes part in the door-to-door canvassing grind, trying to convince local blacks to register for the Freedom Vote. Housing is bare bones and over-crowded, food and money are in short supply, and local law enforcement is a far cry from the Officer Friendlies of other Y-teen tales. The white volunteers are hardly idealized either; Freedom House-mates Ariel and Joe shirk work and eat Polly’s food until she resorts to locking it in her suitcase.

In addition to locking up her cans of juice, Polly learns she must sneak out of the black-owned café when the cops cruise by. She discovers that local black ministers are afraid to let her teen group meet in their churches. Periodically she yearns for the boy she left behind: “What she would not give to have Hank here now!” But in spite of these unfamiliar hardships, Polly perseveres, dodging cops, teaching Freedom classes, and learning lots of new songs. “It’s worth all the discomforts, all the petty annoyances with someone like Ariel, and just rice for supper!” she thinks.

One day there’s a knock on the door and who should it be but Hank, who’s joined the movement in order to pursue Polly, but has learned to love the COFO, SNCC, etc. for themselves: “I realize that butting in down here, as I called it, is the only way conditions can be changed!” In the shabby Freedom House, he snaps the gold basketball charm Polly had returned to him back on her bracelet. They are now in sync, united in love and activism.

This pretty much ends the romantic tension in the book, and the next 95 pages are filled with the day-to-day routine of a civil rights worker in 1964 — constant anxiety, poor living conditions, and police harrassment. Hanks wonders aloud, “What will it be like when we get home and don’t have to be on the lookout for a policeman, a sheriff, or white rabble?” Worn down by the work and food theft, Polly gets a bad cold and moves in with a helpful black family to recuperate. She becomes close with their teenaged kids, Billy and Avis, and even finds a place for her youth group to meet.

Crisis hits when she and Hank are pulled over by a sheriff and arrested on a trumped up charge of vagrancy. Like the well-trained civil rights volunteers they are, they refuse to be finger-printed, demand that they be charged and given a phone call or released, and have an answer for every attack. “‘Seems to me, Sheriff,’” says one deputy, “‘this little girl’s smarter than you.’” Despite this admission, Hank gets beaten up, and they both spend the night in jail. Bailed out, they get chased by a carful of white guys shooting guns. The Freedom House is vandalized.

These two events — the jail time and the car chase — are the book’s peak experiences, as harrowing as this Y-teen version of civil rights activism gets. There’s plenty off-stage violence, but our young couple in love emerge unscathed, eternally focused on the positive. Their case is transferred to federal court, and they head back to Seattle for the Christmas holidays. On the final pages Hank brings the book back to its Y-teen roots, with an oblique marriage proposal: “when you told me not to look back later and ask where was I in 1964 that I didn’t do anything, I started wondering — suppose my own children asked me that years from now? Then I realized that you wouldn’t be the mother of those children unless I had done something.” Polly is suffused with a “glow that spread through her entire being,” as they drive North, leaving Mississippi behind.

Historical Context: This book checks off lots of historically accurate details, while soft-pedaling the very real danger volunteers in Mississippi faced in 1964. John Lewis’s March trilogy conveys the unceasing, horrific level of violence, which left many Freedom Summer volunteers exhibiting the same battle fatigue symptoms displayed by war veterans.

As March and Taylor Branch’s Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years will tell you (or wikipedia and half a dozen other websites if you want the short version), Freedom Summer was the brainchild of Robert Moses (the SNCC activist, not the highway builder) who’d been organizing in Mississippi since 1961. Moses proposed flooding the state with thousands of volunteers who would register voters, organize “Freedom Schools,” and also work on something called the Freedom Vote, part of a strategy to challenge the Mississippi delegation at the 1964 democratic convention.

The first couple hundred volunteers had barely arrived when Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were murdered. Although their deaths fueled the most headlines, the violence didn’t stop there: “there were 80 workers beaten, 1,000 arrests as well as 37 churches bombed or burned,” (per Swarthmore’s Global Non-violent Action Database). Polly learns of violence via the phone tree that connected volunteers, but the book focuses with peppy positivity on the movement’s small victories.

The book also softpedals the tensions between the mostly black organizers and the mostly white volunteers, tensions that caused considerable debate in SNCC: “There had been several complaints about white volunteers trying to take over,” Lewis writes, continuing that activists were irritated because “the press had focused much of their attention on the white workers, often identified by name, shown working alongside nameless blacks.”

Contemporary Critics: “The book has the impact of timeliness and of unbelievable but terrifying experiences but suffers the flaws of most books written to order—too much information overwhelms the plot in the earlier chapters. Characters lack warmth and depth despite the inevitable emotional overtones of the story. The romance between Polly and Hank who joins her in Mississippi is too pallid to be believed. Recommended only until a better fictional account of this stage of our nation’s history is written. Many recently published books of non-fiction on the same subject possibly serve a better purpose.”

— Allie Beth Martin, Director City-County Library, Tulsa, OK. Library Journal, October 15, 1965

My Take: Allie Beth’s “too pallid” line above (was the double entendre intentional?) is accurate, but despite its flaws, I love this book. It illuminates a forgotten corner of history, one of the many campaigns that made up the complex mosaic of civil rights actions in the early sixties. Sure the characters are a bit flat; but it’s a very even-handed flatness. Polly and Hank hardly have more depth than Billy and Avis, their black teen protegés, and the book is blessedly free of those tormented attempts to render Southern black speech phonetically. Also Strachan focuses on the nuts and bolts of the daily activist routine — the preoccupation with food, money, and small discomforts — which give the book a documentary feel, albeit somewhat sanitized. But the book’s real appeal is the way it combines the clichés of teen romance with violent social upheaval. In no other book is the contrast between these two elements so extreme. It’s a like a prom date at a church bombing.

I love the autobiography of Anne Moody, which covers this time period and age group. Your main character sounds like a fictionalized Joan Trumpauer Mulholland, who was one of the students, alongside Anne Moody, in that famous Woolworth’s sit-in at which students had food dumped on their heads.

Yes, same events, such a different perspective. I found that a hard book to read–you really see why civil rights activists in the deep south had battle fatigue symptoms. I do speculate as to whether Strachan got some of her details from talking with actual volunteers, but Joan Trumpauer Mulholland sounds much more of an activist than Polly.

Wow! I had no idea this specific genre existed!!!

Well, it’s only a genre according to me. So far.