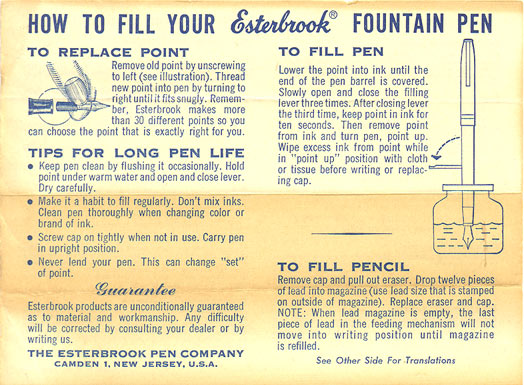

I write with a fountain pen. An Esterbrook plunger model. Not just because it’s eco, or because Patricia Highsmith favored Esterbrooks, or because I’m a luddite contrarian, although all these things are true. I use it because it feels good in my hand and the ink goes from dark to peacock blue as it dries and because every time I have to refill it–lift it off the page, dip it in the ink bottle, pull the plunger down, release the plunger, lift it out, tap it on the bottle lip–my head fills up with the next bunch of words I’m going to write and so I always feel like my hand is racing to keep up with my head and not the reverse.

I write with a fountain pen. An Esterbrook plunger model. Not just because it’s eco, or because Patricia Highsmith favored Esterbrooks, or because I’m a luddite contrarian, although all these things are true. I use it because it feels good in my hand and the ink goes from dark to peacock blue as it dries and because every time I have to refill it–lift it off the page, dip it in the ink bottle, pull the plunger down, release the plunger, lift it out, tap it on the bottle lip–my head fills up with the next bunch of words I’m going to write and so I always feel like my hand is racing to keep up with my head and not the reverse.

I went to see Side by Side Sunday afternoon, a documentary about digital movies versus the photo-chemical kind, and it made me think of the fountain pen, as well as fundamentalists, a book I once read called Shock of the Old, and how watching the film was like seeing my professional life (such as it is or perhaps was) flash before my eyes.

First there were moviolas, rewinds, split reels, splicers; then huge tapes being pushed into the decks of linear editing machines; then Avid (and the Media 100, Premiere, and Final Cut, although those don’t get mentioned). Obsolete formats I can’t watch anymore? Check. Michael Goi says 80 video formats have been developed since video’s inception; I have material on SVHS, Umatic, Hi8, beta, digibeta, dvcam, and dvcpro. I have sat with a color timer discussing how the release print should look and I have changed the color of skin and sky on my computer. And it was hard not to think of projection, sitting in the theatre where I once worked as a projectionist, and remembering the difference between pushing a button on the deck and threading the projector. And sitting in the front row, seeing the sawtooth edges of pixels when interview subjects shrugged their shoulders.

First there were moviolas, rewinds, split reels, splicers; then huge tapes being pushed into the decks of linear editing machines; then Avid (and the Media 100, Premiere, and Final Cut, although those don’t get mentioned). Obsolete formats I can’t watch anymore? Check. Michael Goi says 80 video formats have been developed since video’s inception; I have material on SVHS, Umatic, Hi8, beta, digibeta, dvcam, and dvcpro. I have sat with a color timer discussing how the release print should look and I have changed the color of skin and sky on my computer. And it was hard not to think of projection, sitting in the theatre where I once worked as a projectionist, and remembering the difference between pushing a button on the deck and threading the projector. And sitting in the front row, seeing the sawtooth edges of pixels when interview subjects shrugged their shoulders.

The filmmakers interviewed in the doc might be divided between pro-digital people and doubters, although there was some overlap. The pro-digital people might further be divided into the zealots–those who think, like the fundamentalist christians, that there is one way to salvation and it is through Jesus, only they substitute digital video for Jesus–and the experimenters. The zealots believe that everything is better with digital–there are no downsides. The future is sunny, change is progress, and all problems will be solved very soon. They use words like “power,” “control,” “manipulate”–“manipulate to death” someone says about color correction. They believe that digital film let’s you “do anything” and control everything. Basically, they want to be god, and they believe digital video will lift them to Mount Olympus. They are the control freaks, the neatniks (Soderburgh complains about the dirt and mess of film projection), paranoid men, who dislike sharing their power with anyone else. I used to think that no one could have a bigger ego than James Cameron, but that was before I saw the interview with George Lucas. George Lucas doesn’t want to entertain audiences; he wants to subjugate them to his vision of the universe.

The experimenters were easier to swallow (although Danny Boyle apparently belongs to that culture that takes its aged and when they can no longer chew, puts them out on mountain tops to die. If you don’t want to jump on the digital bandwagon, he says in essence, let the vultures pick out your eyes and the sun bleach your bones). People like Bradford Young (who made Pariah so beautiful) may someday reconcile me to the decline of celluloid. They talk less about power and more about possibility–the shots they couldn’t get before, the films that became affordable.

But my heart is with the doubters. Anne Coates (Yes! Finally a woman!) and her story about the planned dissolve in Lawrence of Arabia turning into a straight cut. Robert Downey Junior protesting with mason jars of piss; the cinematographer who likes the feel of film. They talk about accidents, discoveries, leaps of faith, rhythm. They talk about pauses–the pause when you change the film magazine, the pause when you rewind the film to your edit mark.

Which brings me back to pens. One of the things I hated most about editing for money was the constant pressure to be fast, the unarticulated assumption that pausing to breathe and think was unproductive, and that anything that made working faster possible was in and of itself good. But creativity, it turns out, is not a prize won by speed. Ideas may occasionally race through my head, and my hand may occasionally race across the page, but that is the systole to the diastolic moments of doing nothing.

Someone in the film says “there will always be stories and storytelling.” Duh! That’s not what I’m worried about. It’s whether I’ll be able to breathe while telling them.